Nuclear physics and war

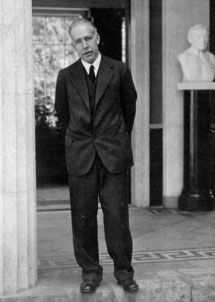

In the early 1930s, Niels Bohr’s interest in theoretical physics turned from the outer part of the atom to the nucleus. His research took a new direction and he changed the priorities of his institute.

Protons and electrons were already known and in 1932 James Chadwick discovered the last of the atomic building blocks, the neutron. After this discovery, nuclear physics developed rapidly. The same year that the neutron was discovered, a nuclear reaction was made for the first time using fast, charged particles from an accelerator. The following year, Enrico Fermi produced artificial radioactive materials by bombarding known elements with neutrons. Some of these substances were so short-lived that Enrico Fermi and his team had to rush down the laboratory hallway to bring them to the counters before the disappeared completely..

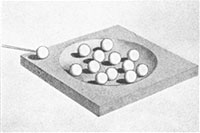

Niels Bohr illustrated the formation of compound nuclei with this model: A marble is rolled down into a dish with some other marbles. Repeated collisions quickly distribute the energy of the injected marble between the other marbles in the dish. It is therefor unlikely that a single marble will gather enough energy again to hop of the edge. A marble, that is to say, a neutron is thus captured.

In 1936, Niels Bohr formulated his revolutionary compound nucleus model, whereby the nucleus is transferred to a temporarily unstable compound state during a reaction, before it returns to a stable state when the reaction is over. The model explains why a neutron is captured instead of being rereleased. Together with Niels Bohr’s liquid drop model, which he formulated in 1937, the theory also explains the fission process.

In 1939, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann discovered that reaction products were produced at lower atomic numbers when you irradiated uranium with neutrons. They had discovered fission and this paved the way for the generation of nuclear chain reactions. This set off frantic research activity on both sides of the Atlantic. In particular, Niels Bohr made a significant contribution to the theoretical understanding of fission during an extended visit to Princeton.

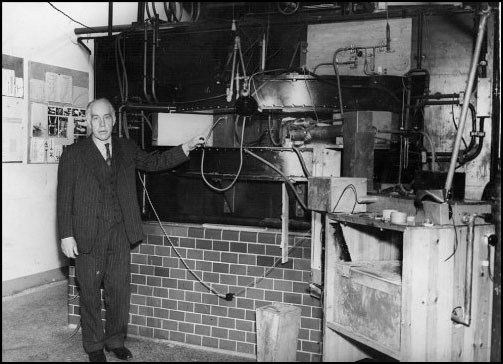

Niels Bohr quickly realized how big a role the irradiation of elements with neutrons would come to play and he organized his institute accordingly. An accelerator that could produce 1 million volts and a cyclotron were placed in a new wing, which was completed in 1939. It was the first cyclotron to come into use in Europe.

Originally, Niels Bohr did not bother himself with politics. But after the Nazis took power in Germany in 1933, this changed. In the following years, he helped several scientists escape Germany. In September 1939, the Second World War broke out and when Denmark was occupied in 1940, Niels Bohr chose to stay rather than flee.

The Niels Bohr Institute occupied by the Germans.

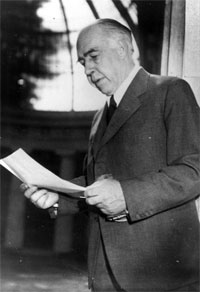

Even though Niels Bohr was of the leading contributors to the new nuclear physics, he did not believe it would be possible to develop an atomic bomb in the near future. This was the basis for his rejection of a secret invitation to move to England in early 1943, when he was forced to flee from occupied Denmark in October of the same year, he changed his mind and accepted the invitation. After a short stay in Sweden, he was flown to England and from there he came to the United States as a member of the British group of scientists who participated in the work to produce a nuclear weapon.

While Niels Bohr agreed to participate in the project, he started a campaign on his own initiative to convince British and American leaders that the Soviet Union should be informed of the project’s existence before the end of the war. For Niels Bohr, the existence of weapons of mass destruction necessitated an open world where all scientific and technical information should be shared between nations to avoid unwarranted suspicion and fatal misunderstandings. Niels Bohr fought for this cause until his death in 1962.

|

|

|

|